Andhra Pradesh’s power sector is going through a second phase of reforms. The first (1999-2004) was widely seen as focused on privatization of electricity distribution; this time the goal is to ensure affordable and reliable power supply for all. To do so, Chief Minister Chandrababu Naidu has pledged to keep retail tariffs unchanged in the coming years for all consumer categories, while improving the quality of supply and service.

At present, the central government is pushing strongly to raise retail tariffs to reflect the rising costs of supply, a target set for states under the UDAY scheme for discoms’ financial turnaround. This makes Andhra Pradesh’s plan—to improve electricity without any additional cost burden on the consumers—particularly intriguing. Can Naidu pull off this trick while avoiding negative consequences for the state’s electricity sector? What are the consequences of failure?

The context for this latest gambit is the reform effort of 1999-2004. Despite backing by the chief minister, supportive and skilled regulators and utilities, and the central government, the plan to improve discoms’ health through tariff and management reforms did not receive public support. Although discoms registered efficiency gains, the public focused on the accompanying tariff hikes, which caused mass agitation. Some have suggested this was central to Naidu’s defeat in the 2004 state assembly election.

In his return to power in 2014 in a smaller Andhra Pradesh, Naidu has devised a reframed reform strategy. First, consumers are at the centre of reforms and are promised high-quality service at affordable prices. Notably, however, this does not include promises of a 24/7 supply of free power to farmers, as in Telangana.

Second, the reform relies on disruptive technologies to bring down discoms’ power bills through a five-point strategy:

- Improve supply through enhanced renewable energy (RE) generation, energy storage technologies, and full capacity utilisation of conventional power plants;

- Implement energy efficiency measures;

- Strengthen the transmission and distribution (T&D) network to bring down losses to below 6 percent;

- Adopt information technology for better consumer services; and

- Improve financial management of power projects, including loan swaps.

There are early signs of progress. The state has achieved 7 GWs of RE installed capacity, which is 10 percent of national RE capacity and 30 percent of the state’s total generation capacity. To complement RE capacity, Andhra Pradesh has inaugurated the first thermal battery plant of India and allocated more than 100 acres for energy storage projects. The state has set a target of 10 lakh (1 million) electric vehicles on the road by 2023, backed by a dedicated electric mobility policy and planned investment of Rs 30,000 crore (300 billion rupees). Andhra Pradesh has emerged as a national front-runner in the State Energy Efficiency Preparedness Index. To improve efficiency and reliability of the T&D network, the state initiated a $570 million project last year, with donor assistance.

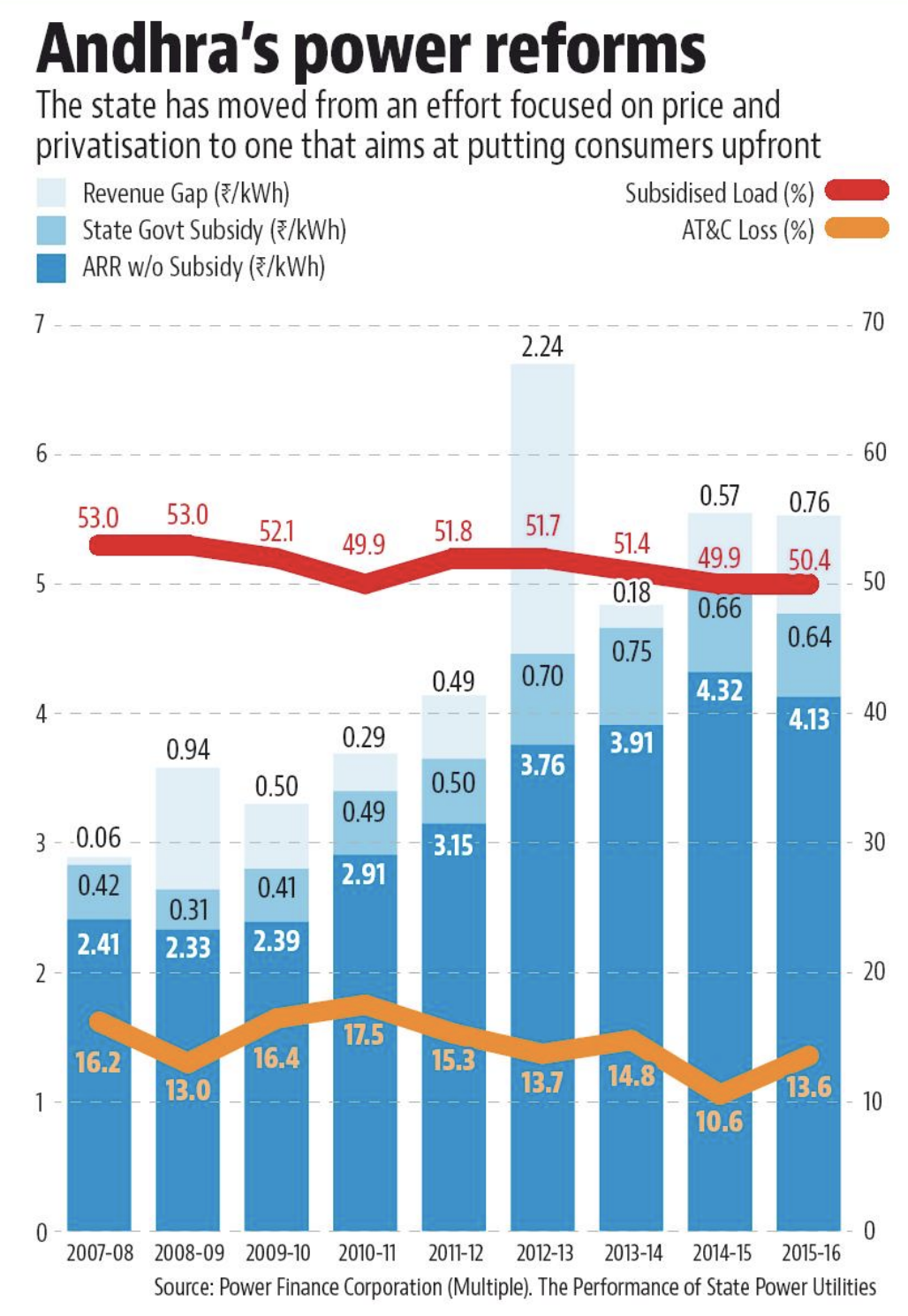

What works in the state’s favour is that it has some breathing room to manoeuvre because of several reasons. After the bifurcation of the state, Andhra Pradesh gained from a slight reduction in subsidised load (domestic and agriculture) and aggregate technical and commercial (AT&C) losses. Since it is a relatively wealthy state, it has managed a persistent revenue gap by increased state subvention, from 12 percent of discoms’ revenue requirement in 2014-15 and 2015-16 to 19 percent in 2018-19, as illustrated below. This has prevented a decline in quality of service.

In September 2018, the per-unit revenue gap was 0.06 rupees, one-fifth the national average, and AT&C losses were 11 percent, half the national average, as reported by the UDAY portal. These developments make Andhra Pradesh a leader in UDAY target achievements while providing the fiscal space to manage the political demands for explicit subsidies.  However, for long-term gains, the state will need to use this breathing room to bring down the costs of supply and create enough demand for the additional power capacity it is adding through RE and augmented capacity utilisation. Naidu hopes his plans for industrialisation will absorb the surplus power. Whether this works will depend on growth in industrialisation as well as proper resource planning for the additional generation capacity.

However, for long-term gains, the state will need to use this breathing room to bring down the costs of supply and create enough demand for the additional power capacity it is adding through RE and augmented capacity utilisation. Naidu hopes his plans for industrialisation will absorb the surplus power. Whether this works will depend on growth in industrialisation as well as proper resource planning for the additional generation capacity.

Notably, Andhra Pradesh has sought to capture the gains of falling RE generation costs as technology improves. The counter, and more problematic, story is that industrial consumers would leave the grid to capture these gains through direct installation of RE, which would cut into the cross-subsidy available for poorer customers. Andhra Pradesh is seeking to manage this transition by proactively adopting these disruptive technologies in an effort to reduce the power bills for all, but also retaining industry through improved quality and a stable tariff.

In this tale of two reforms, Andhra Pradesh has moved from a price- and privatisation-focused effort to one that aims to put consumers up front. If it fails, the results would be dismal and all too familiar: low tariffs combined with growing stranded capacity as new generation finds no takers, and declines in cross-subsidies as industrial customers flee. But the reforms are designed specifically and deliberately to avoid these traps, which is what makes them interesting. If Andhra Pradesh succeeds, it will signal an alternative, consumer welfare-focused model of power reforms. While it is too early to predict success, this is an effort worth watching.

Ashwini K. Swain is executive director of the Centre for Energy, Environment & Resources and a visiting fellow at the Centre for Policy Research. This research is based on work presented in full in the book Mapping Power: The Political Economy of Electricity in India’s States, edited by Navroz K. Dubash, Sunila Kale, and Ranjit Bharvirkar.

A version of this blog post first appeared in the Hindustan Times.