On 28 June, a committee made up of members of European Parliament finally signed off on a new EU Renewable Energy Directive (RED III), the landmark law that aims to speed up the deployment of renewable energy across the EU. This paves the way for a final plenary vote in September and final rubber stamping from Member States after that. Once the Parliament and Council formally adopt the deal, it will replace 2018’s RED II.

The provisional political agreement reached back in March garnered plenty of media attention – in part because of last-minute political hold-ups to its formal signing off – but also for its increase to the headline target: the EU has now set itself on a binding path to double its share of renewables in final energy consumption by 2030, from 22% in 2020 to 42.5%. This is a large increase in ambition from the previous target of 32%. To achieve it, the share of renewables in heating and cooling, around half of the EU’s final energy consumption, should also reach around 43% by 2030.

However, despite overcoming weeks of political roadblocks to win over the Parliament’s Committee on Industry, Research and Energy on 28 June, the RED III agreement contains important, unresolved issues that hamper its effectiveness for renewable heating and cooling. Member States can fill these gaps with more ambitious efforts, but they must move quickly.

EU heating and cooling: RED struggles to ramp up ambition

RED II aimed to address heating and cooling by setting an indicative sub-target for Member States to gradually increase the use of renewables for purposes such as space heating and cooling, industrial process heat and more. The updated RED III is set to make this sub-target binding. Once it becomes law, each Member State must achieve an increase in its share of renewable heating and cooling: an annual 0.8 percentage point increase from 2021 to 2025 and 1.1 percentage points annually from 2026 to 2030. For example, if a country’s share is 20% in 2023, then it must be 20.8% in 2024.

Unfortunately, RED III’s binding targets do little more than follow this existing, business-as-usual path.

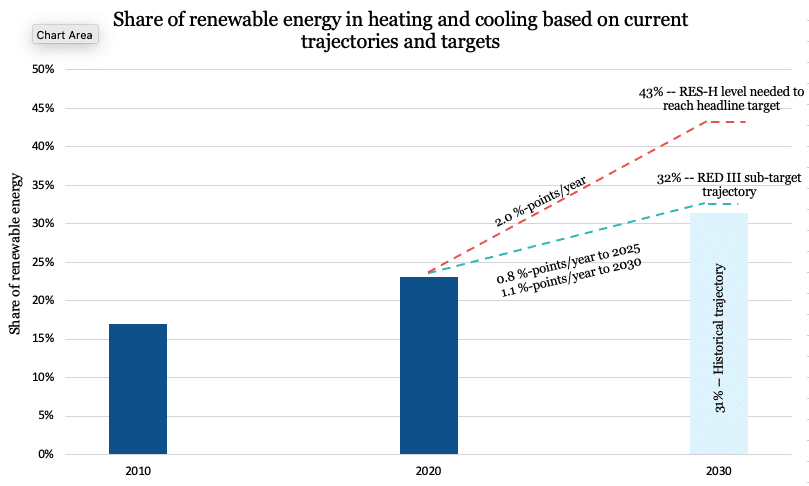

This target falls short of putting Europe on a decarbonisation pathway for heating in line with the bloc’s climate targets, however. RAP’s 2022 publication Metrics Matter explored the math behind the previous sub-target in detail. We found that the share of renewables in heating and cooling has been rising at around 0.6 percentage points per year over the previous decade. With renewables currently contributing 23% to heating and cooling, it puts the EU on track to only reach about 31% by 2030 under the current trajectory.

Unfortunately, RED III’s binding targets do little more than follow this existing, business-as-usual path, as shown in the figure below. Our calculations show that if the EU achieves the bare minimum percentage-point increases outlined in the RED III, it will still only reach a renewable share of 32% in heating and cooling by 2030, just above the status quo trajectory of 31%. In other words, the EU has set itself a target that it can achieve while continuing with business as usual.

Although the picture may look different when broken down by Member State, as the binding targets apply to each country individually, RAP calculations show that an increase of at least 2.0 percentage points annually – starting in 2020 – would be necessary to achieve a level high enough to reach the RED III headline target.

Not all renewable energy technologies are created equal

Another issue with RED III is which renewable energy technologies will be used. Here, a major sticking point is biomass. By and large, over the past decade, the biggest increases of renewables in heating have been observed in countries where biomass constitutes a significant share of heat production, especially in district heating. Not all Member States can follow suit, nor should they, as the potential for biomass use is limited and can be accompanied by sustainability issues. That means a new approach is needed, and electrification of heat – for both individual heating systems and district heating – is widely expected to play a central role.

Yet heating technologies using electricity have previously been disadvantaged in RED II for two main reasons. One, any electricity used for heating (and cooling) did not count towards the heat target in RED II. It simply was not considered in the sector; all renewable electricity statistically was placed in the power sector bucket. Concerning electric heat pumps, only the ambient heat harnessed by the heat pump was classified as “renewable,” whereas the electricity used to drive the process, even if renewables-based, was not. This means that, with electrification technologies unable to fully count towards meeting the EU’s heating target, there was less incentive to deploy them, and more incentive to install alternatives, including combustion technologies for biomass.

In fact, renewable combustion technologies are heavily favoured due to a second key reason: the way the units of renewable heating are counted. The methodology to determine the contribution of each renewable energy technology accounts for the energy harnessed to make the heat (for example, by burning biomass), not the useful heat itself. In other words, it does not reward efficiency.

Member States can ensure that the right incentives are in place to encourage efficient heating systems over inefficient combustion.

Consider an application where you need 100 units of heat. A 50% efficient furnace would need 200 units of biomass to produce this heat. Yet, those 200 units of biomass are counted as “renewable energy consumption.” While in the case of an electric heat pump with an efficiency of 300% (the coefficient of performance is 3), the 100 units of heat could be produced using only 33 units of electricity and 67 units of ambient heat. Previously, RED II only counted the 67 units of ambient heat towards the renewable energy target; the 33 units of electricity – even if it came from renewable sources – did not count. Counterproductively, this punishes heat pumps for being efficient by undervaluing their contribution to the renewable energy target.

Member States have important tools to hand

Fortunately, RED III seems to have addressed the calculation methodology issue. It now considers renewable electricity used for EU heating and cooling as contributing to the target if devices have an efficiency above 100%. This tricky wording avoids crediting inefficient electric resistance heaters with a renewable energy contribution.

What still remains unresolved, however, is the failure to fully value electrification technologies. The least-efficient devices are still credited with producing the most renewable heat. Efficient devices such as heat pumps have received a small boost under RED III, but combustion technologies retain a serious advantage and are likely to be further deployed to help meet EU Member States’ binding renewable heating and cooling targets.

Although it is now too late to adjust the RED III text, Member States can nevertheless ensure that the right incentives are in place at national level to encourage efficient heating systems over inefficient combustion. That means easing permitting, investing in skills and manufacturing, providing targeted support to low-income households and rebalancing taxes and levies from electricity onto fossil fuels.