Energy-only markets will enable the integration of the European electricity market and development of the flexible resources needed to support a decarbonised future. Philip Baker and Michael Hogan offer a critique to RTE’s impact assessment of the French capacity market.

Energy-only markets (EoM) are the building blocks of Europe’s integrated electricity market. Not only do they avoid distortion in cross-zonal trading, they encourage development of flexible resources such as storage and demand response needed to ensure supply reliability in a low-carbon future. This is possible because EoMs are meant to allow energy prices to reflect the value our security of supply standards assume customers place on uninterrupted supply.

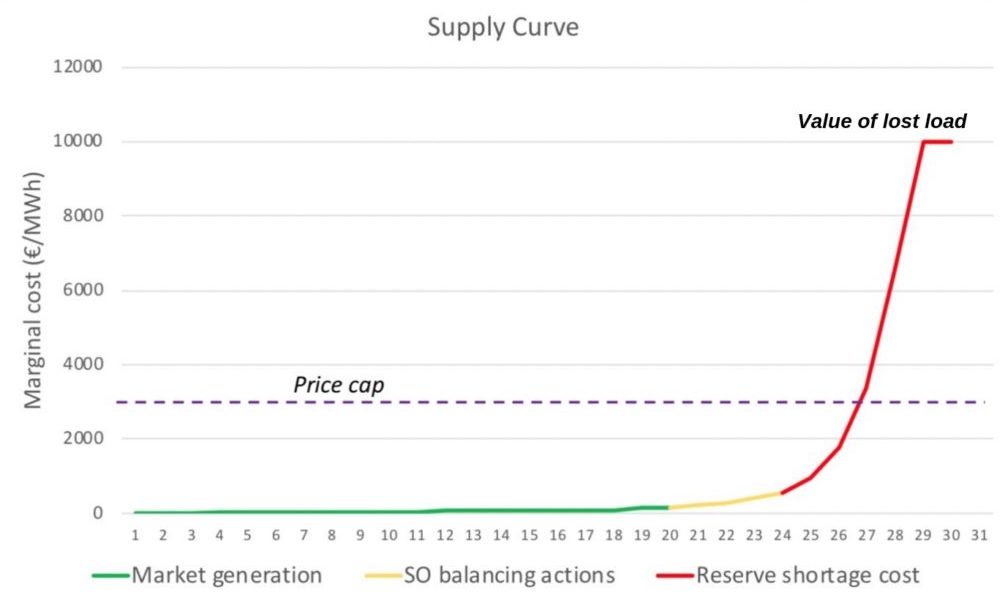

If EoMs (and the bilateral trade they incentivise) are to be relied upon to support needed investment, investors need to be confident that regulatory and political interference will be avoided and that, when resources are scarce, wholesale energy prices will be allowed to rise to reflect the real value of energy. We are not at this point yet—most of Europe’s energy markets have price caps or other features that prevent generation from accessing this scarcity value via infra-marginal rent (that is, the difference between the clearing price, which is meant to reflect the marginal cost of energy, and a generator’s marginal production cost). This also prevents wholesale buyers from being exposed to the true marginal cost, which suppresses the bilateral trading that underpins the effectiveness of the EoM.

The Commission’s proposed Clean Energy for All Europeans package therefore accepts that additional investment support in the form of capacity markets may be required as a temporary measure. The emphasis is very much on “temporary.” Before the introduction of a capacity market can be justified, Member States must establish a clear need for new investment, a clear case that the market will not support the needed investment, and a programme of market reform to provide a realistic exit strategy.

However, a recent report by RTE, the French system operator, contradicts the Commission’s belief that EoMs are a practical and cost-effective means of ensuring reliability. Firstly, RTE questions the assumption that removing price caps and allowing energy prices to rise to high levels—potentially to the value of lost load when demand for energy and needed reserves exceeds the supply of both—will be acceptable from a political or social justice point of view. Secondly, RTE asserts that capacity markets, such as that introduced in France, represent a more cost-effective means of delivering generation adequacy than an EoM. In other words, rather than being a necessary evil to be discontinued as soon as is practical, RTE asserts that capacity markets are the more acceptable option and should become a common and permanent market feature.

Europe has yet to test the political and social acceptability of real wholesale price volatility, owing largely to a substantial overhang of excess supply. However, evidence from Texas (ERCOT) and Eastern Australia (National Energy Market) suggests that EoMs can operate successfully, delivering the resources necessary to ensure reliable supply without price volatility posing unacceptable risks to consumers. Bilateral contracting by suppliers to manage market risks provides a buffer between consumers and the wholesale market. This gives consumers the choice of whether or not to manage and benefit from exposure to energy price volatility, either directly or via energy service aggregators.

With regard to the second issue, RTE claims that capacity markets offer a more cost-effective means of ensuring supply reliability. The principal rationale for this assertion is that guaranteed capacity payments via a capacity mechanism reduce various risks for investors, thereby reducing the cost of capital to provide the necessary generation capacity. While capacity payments are likely to reduce investor risks, RTE’s assumption that the costs associated with those risks magically disappear with the introduction of a capacity market is flawed. In most cases, those costs do not disappear, they are transferred to consumers. Not only do they not disappear, but consumers are far less capable of assessing and managing those risks, meaning the costs increase by virtue of their being shifted to consumers.

No capacity market design will be perfect, and there will always be a risk of over-procurement. This is especially true when capacity requirements are set by the transmission system operator or by governments, who bear the reputational and political consequences of the extremely rare supply shortfalls anticipated by long-standing resource adequacy standards but not the cost of overinsuring against them. This asymmetrical incentive leads to a tendency to overestimate demand or make other conservative assumptions that lead to the provision of uneconomic capacity.

An example of the tendency of transmission system operators to take a conservative approach can be seen in the case of Great Britain’s capacity market. Despite financial incentives, National Grid has consistently overestimated peak demand to the tune of around 1.5 GW. This, together with conservative assumptions about plant availability and sensitivities, has resulted in levels of security well in excess of that needed to comply with the accepted reliability standard—forcing consumers to pay for capacity that, according to the government’s publicly stated standard, is not value for money.

A conservative approach is less likely to be seen in an EoM, where market participants are exposed to the consequences of overprovision of capacity though reduced volumes (reduced operational hours), reduced energy prices, or both. Market participants who are financially exposed to the consequences of their decisions are far better placed to manage the associated risks than are consumers.

RTE also makes an unfair comparison between a perfect capacity market—like Father Christmas, a figment of the imagination—and an imperfect EoM that overprovides capacity due to a mismatch between the reliability standard and the assumed value of lost load. Intuitively, the greater risk would be of an EoM providing too little, rather than too much, capacity. By the same token, when the cost of oversupply is stripped out and the supposed cost-of-capital advantage of a capacity market is ignored for the reasons given above, then the social welfare benefits of both seem similar. This is an outcome to be expected if the aim of the capacity market is to simply replace the “missing money” associated with an imperfect EoM design.

There are also other intuitively suspect outcomes of the RTE study that require further explanation. One such outcome is the conclusion that an EoM with a high price cap (e.g., 20,000 euros per MWh) is likely to deliver less capacity from demand response and more from open cycle gas turbine plants than a capacity market. Rather, exactly the opposite outcome is to be expected, i.e., that reliance on high-value but uncertain events in an EoM, rather than guaranteed income via a capacity market, would favour the development of relatively low-capital-cost options such as demand response over higher-capital-cost alternatives, such as open cycle or even combined-cycle gas turbine plant. Furthermore, the design of an administrative procurement process such as a capacity market is more likely to exclude non-traditional alternatives through participation rules designed around more familiar solutions.

In summary, therefore, we support the Commission’s view that EoMs (including shortage pricing mechanisms to ensure demand for reliability is reflected in energy prices) represent the most appropriate market design in the transition to a clean energy system. Allowing energy prices to reflect the real value of reliable energy, and to rise when the resources needed to provide that reliable service are scarce, will eradicate the missing money problem and encourage the development of the flexible resources, such as demand response and storage, that are necessary to support the energy transition. Capacity markets, on the other hand, will perpetuate the missing money problem, depressing energy prices and leading to higher peak demand and capacity requirements. Capacity markets seem to be about supporting existing assets and inflexible technologies, and less about delivering the new flexible capacity that we need for our low-carbon future.

EoMs are also clearly more consistent with the concept of an integrated European electricity system and market. The formation of energy prices is harmonised across borders, while the introduction of capacity markets—often very different in design, reflecting the particular needs of individual Member States—will distort energy prices and undermine cross-border trade.

A version of this article originally appeared on Euractiv. Photo by Russ Allison Loar/Flickr