Raoul Dufy’s 1937 fresco La Fée Électricité — an arresting 600 square metre tribute to “the great adventure of electricity” — depicts science and technology leaps such as Faraday’s discovery of electromagnetic induction, Gramme’s direct current dynamo, Baudot’s telegraph, and Edison’s incandescent light bulb. These developments changed the world in ways that were previously unfathomable.

Tackling the climate crisis while mitigating the impacts of the war in Ukraine and skyrocketing energy prices will require Europe’s policymakers to champion a new class of energy pioneers in the months and years ahead: households.

A spectrum of challenges

Europe faces a step-change within a step-change. Securing a clean, affordable and reliable energy system is no longer a case of moving fast without breaking things. We must now accelerate while fixing things.

This means ramping up green generation at an unprecedented scale and pace, shunning imported gas without over-relying on expensive alternatives — such as hydrogen in its rainbow of varieties — or relapsing on brown fuels. We also need to secure energy supply, ensure grid reliability and help families and businesses stay out of the red.

No matter how many supply-side resources we pour into the mix, the perfect blend will elude us until we stop treating demand-side flexibility as a final flourish of glitter.

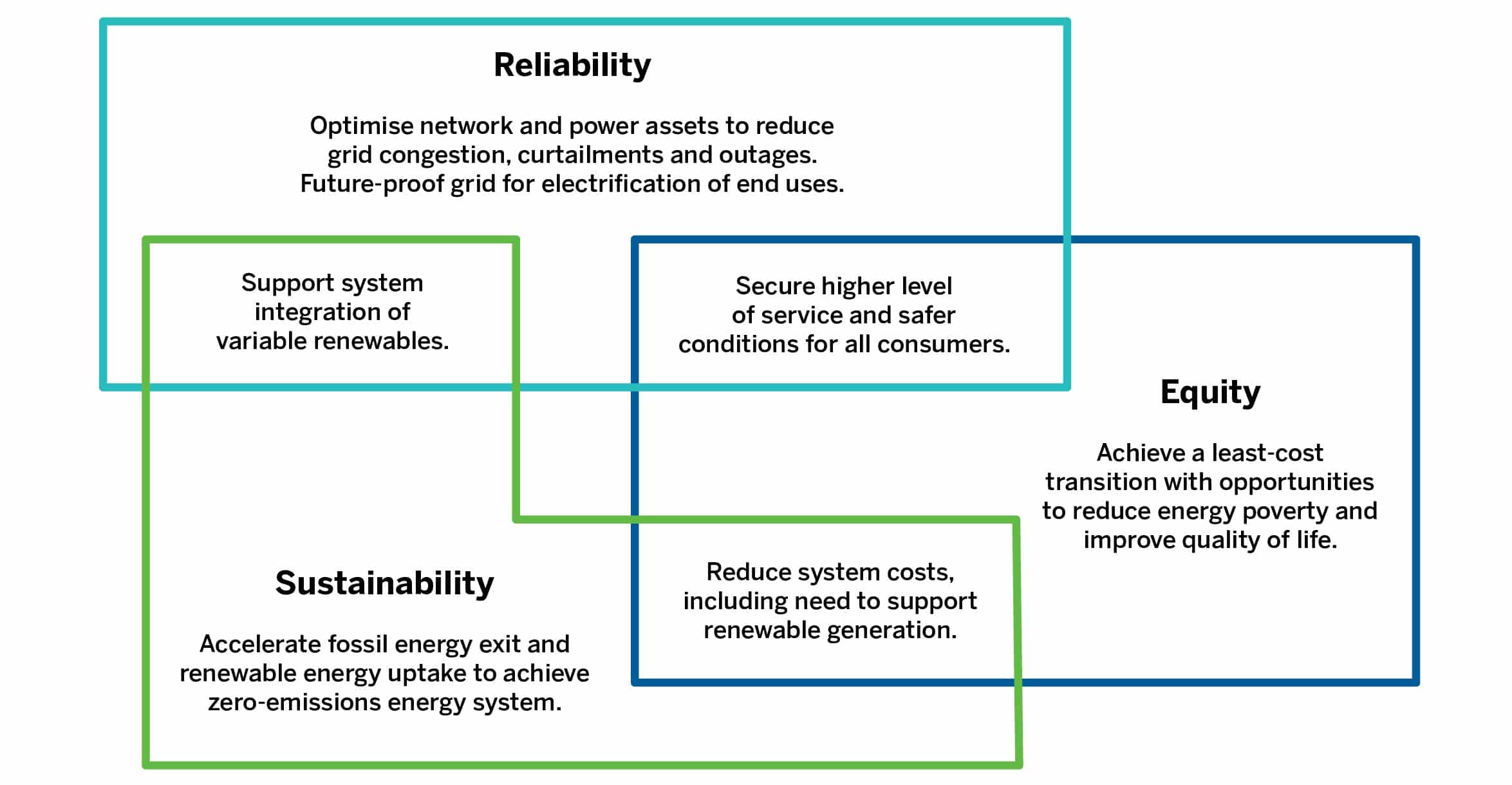

In fact, it is more like the primer — often unseen but foundational to reliability, managing price volatility, enhancing grid performance, efficiently integrating renewables, facilitating newly electrified technologies and reducing cost. Flexibility adds adhesion and endurance to the core principles of energy policy.

Demand-side flexibility binds energy, climate and social objectives together.

Putting households in the frame

Demand-side flexibility means energy users changing how and when they use electricity in return for financial reward. They offer flexibility by drawing power from the grid at different times and by utilising energy efficiency, onsite generation and onsite storage, including electric vehicle batteries.

We need lots of flexibility and we need it now. The IEA estimates that, to reach net-zero emissions by 2050, a ten-fold increase of demand-side resources is required worldwide by 2030, compared with 2020 levels.

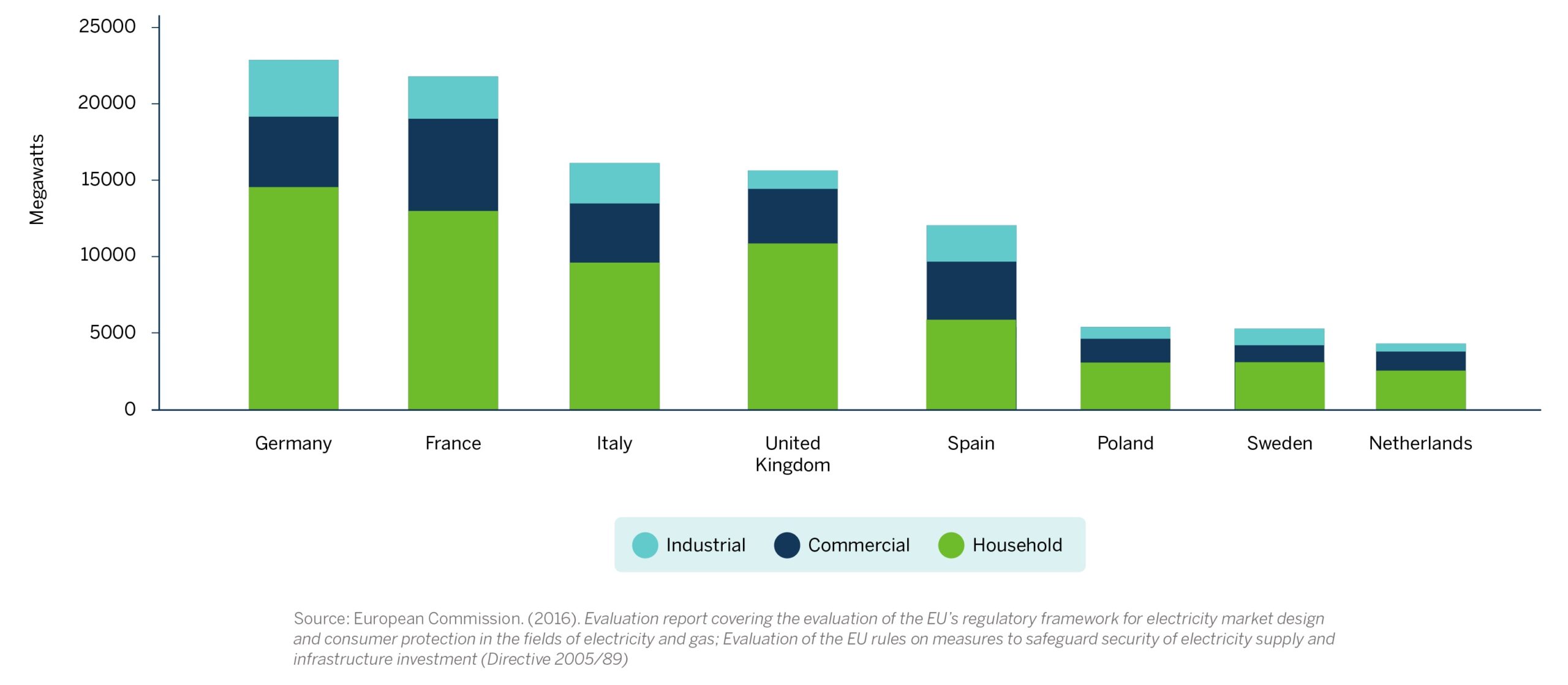

Industrial response receives most of the policy attention on the demand side, which is still only a fraction of that dedicated to supply-side resources. However, European Commission analysis concluded that the greatest potential for additional customer flexibility in 2030 actually lies within homes.

This is due to the, as yet untapped nature of this sector, plus projected electrification and digitalisation of buildings and vehicles. The proportions in the graph below are striking—even though the capacity levels themselves are likely to be a significant underestimate, given the fast-paced technology and market evolution since the 2016 study.

Policy proposals

To take advantage of these untapped resources, there are three policy actions that should be enacted.

Firstly, make flexibility effortless and stress-free. Policymakers need to stop putting the onus on individuals to solve structural problems. People are busy; they have kids to get to school, shifts to work and boilers and cars that fail at the worst times. It is not their job to become energy market experts, it is the job of energy market experts to ensure that people make decisions — even unconscious ones — that boost flexibility and reduce energy bills.

There should be an EU-wide “mandate for smartness,” requiring products and buildings to be electrified and “flex-ready,” with clear labelling and high-quality customer support. Deployment schemes are urgently required, including subsidies to fast-track uptake and drive down future costs, replicating the success of renewables.

The regulators’ role is to ensure digital inclusivity of marginalised and vulnerable groups and to adapt customer protection rules so they keep up with new retail offers, without picking winners or stifling innovation.

Secondly, allow wholesale pricing to reflect the true value of flexibility. To uncover the value of flexibility and reveal its full potential, wholesale electricity prices should reflect real-time conditions on the power system.

Interventions such as price caps mask the increased costs caused by inflexibility, reducing incentives for efficient actions. Households should be rewarded to increase demand when there is a surplus of renewable generation, for example, but measures like minimum price guarantees prevent payment via the wholesale market.

Safeguards such as supplier hedging, price relief mechanisms for extreme events and targeted support for low-income customers become increasingly important. The baseline, however, should be wholesale pricing and smart network tariffs that reward flexibility in a fair and non-discriminatory way. This creates a positive feedback loop of households embracing flexible assets and seeing tangible benefits, which further incentivises flexibility.

Finally, develop robust metrics for flexibility. Europe lacks a common methodology for assessing and quantifying the multi-faceted benefits of customer flexibility.

Unless we make this value visible and measure it consistently and fairly, we cannot reliably assess flexibility potential or design mechanisms to unlock it. Developing robust metrics supports policies that can accelerate flexibility deployment such as targets, trading platforms and obligations on suppliers to procure demand-side capacity. Standardisation also enables progress to be tracked across Member States.

To create a masterpiece, start with a masterplan

“Art is not what you see, but what you make others see.” – Edgar Degas

Flexibility is a system resource, activating it requires systems thinking. That does not mean treating households like mindless cogs in the machine — a new social contract must be crafted for the age of automation, upheld by equity, agency and opportunity.

Europe’s policymakers should take in the whole picture, rooting out market distortions, barriers to access and bad practices, while proactively showcasing and replicating positive examples of household flexibility, beyond pilot schemes.

If the artwork La Fée Électricité were recreated in the year 2035, what would we see? The fresco could show millions of homes, interacting seamlessly with the power system, for the benefit of people and planet alike.

One thing is certain, we are going to need a bigger wall.

A version of this article originally appeared on Foresight Climate & Energy.

Photo: Guillaume Baviere via Flickr Creative Commons