Much of the controversy associated with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) proposed Clean Power Plan has to do with disputes about whether the agency has the authority to set greenhouse gas emissions limits for power plants based only on what is achievable “inside the fence” of regulated power plants, or both inside and outside the fence.

We take no position on the legal merits of these arguments. However, there is value in considering the implications for states if they choose to delay action on the Clean Power Plan, or ignore outside-the-fence opportunities altogether, should EPA’s interpretations of the law be upheld. Here, we look at several examples of what it might take for states to comply with the Clean Power Plan without using energy efficiency as a strategy.

Clean Power Plan Arithmetic

The emissions rates that EPA proposed for each state are based in part on calculated estimates of the amount of renewable energy and energy efficiency (in the lingo of the Clean Power Plan, Building Blocks 3 and 4, respectively) that could feasibly be deployed in the state each year from 2017 through 2030. EPA also assumes that states can lower emissions rates by making coal-fired electric generating units (EGUs) six percent more efficient (Building Block 1) and by changing dispatch decisions to use natural-gas-fired combined cycle (NGCC) EGUs more frequently and coal-fired EGUs less frequently (Building Block 2). For Building Block 2, EPA limits the amount of re-dispatch that is assumed to be possible by limiting NGCC capacity factors to 70 percent.

If EPA finalizes the Clean Power Plan rules in a form similar to the proposal and the rules survive the inevitable legal challenges, states won’t have to deploy the assumed amounts of renewable energy and energy efficiency. However, if states deploy less of either resource, they will have to do more of something else to reach their proposed targets. (States have a wide array of technological and policy options available for reducing greenhouse gas emissions from the power sector.) Using the assumptions and targets described in the proposed rules, we illustrate this by considering how Arkansas and Utah would fare without energy efficiency.

Arkansas, Proposed 2030 Emissions Rate: 910 lbs/MWh

EPA assumes:

- Arkansas can achieve 4.9 million MWh in annual savings in 2030 from end-use energy efficiency policies and programs.

- All of the NGCC capacity in Arkansas will operate at a 70 percent capacity factor on an annual basis, meaning additional re-dispatch from coal to gas is not considered feasible.

If Arkansas conforms to EPA’s assumptions about electricity demand, fossil fuel generation, and renewable generation in 2030, but does not get any savings from energy efficiency programs, its emissions rate will be 996 lbs/MWh—exceeding its Clean Power Plan goal.

Absent investment in energy efficiency resources, Arkansas could in theory try to achieve its 910 lbs/MWh rate target by improving upon EPA’s assumptions regarding other building blocks, by doing any one of the following:

- Building Block 1: Improve average heat rate of coal-fired EGUs by 25 percent, instead of the assumed six percent (Arkansas officials feel that even a six percent improvement is infeasible);

- Building Block 3: Increase renewable energy by an additional 4.9 million MWh (i.e., a 104 percent increase over the amount of renewable energy assumed by EPA); or

- Other Building Blocks: Reduce emissions using other strategies, e.g., decrease coal generation by an additional 3.6 million MWh—roughly equivalent to shutting down a 550 MW coal-fired EGU—and reduce the state’s net power exports by an equal amount.

Utah, Proposed 2030 Emissions Rate: 1,322 lbs/MWh

EPA assumes:

- Utah can achieve 3.5 million MWh in annual savings in 2030 from end-use energy efficiency programs.

- All of the NGCC capacity in Utah will operate at a 70 percent capacity factor on an annual basis, meaning additional re-dispatch from coal to gas is not considered feasible.

Utah will also exceed its Clean Power Plan goal, if it conforms to all of EPA’s assumptions about electricity demand, fossil fuel generation, and renewable energy generation in 2030, but does not get any savings from energy efficiency programs (its emissions rate will be 1,454 lbs/MWh).

Utah could try to achieve its 1,322 lbs/MWh rate target without energy efficiency, by doing any one of the following:

- Building Block 1: Improve average heat rate of coal-fired EGUs by 17 percent instead of the assumed six percent;

- Building Block 3: Increase renewable energy generation by an additional 3.5 million MWh (i.e., a 146 percent increase in renewable energy); or

- Other Building Blocks: Reduce emissions using strategies that are not part of EPA’s best system of emissions reductions, e.g., decrease coal generation by an additional 7.4 million MWh—roughly equivalent to shutting down two 500 MW coal-fired EGUs—and reduce the state’s net power exports an equal amount.

The Grass Is Greener Beyond the Fence

With numerous public comments on the Clean Power Plan arguing that EPA is wrong to assume the feasibility of a six percent improvement in the average heat rate of coal-fired EGUs, we note that virtually all stakeholders would likely agree that a 17 percent or 25 percent improvement is not achievable across an entire fleet of EGUs. In other words, neither Arkansas nor Utah could realistically replace energy efficiency measures entirely with inside-the-fence, Building Block 1 emissions reductions.

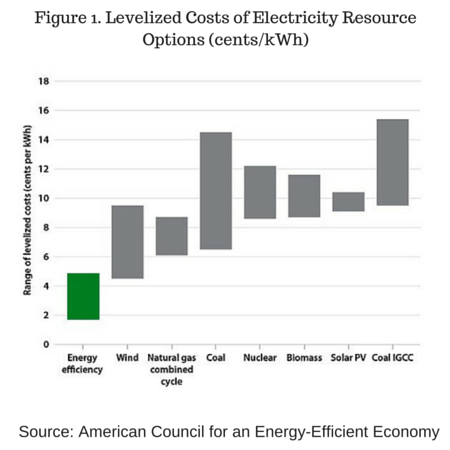

While it might be feasible for a state to increase renewable energy (Building Block 3) by the amount that it won’t be getting from energy efficiency, the state will almost certainly pay more than necessary to achieve the same emissions rate goal. The cost of saving electricity averages 2.8 cents per kWh—about one-half to one-third the cost of generating electricity with any alternative option (Figure 1).

As in Arkansas and Utah, most states will be hard-pressed to achieve their assigned emissions targets if they act solely “inside the fence.” States that overlook energy efficiency as a compliance strategy will paint themselves into a corner, leaving only more expensive compliance options. They will also miss out on the non-climate-related benefits of energy efficiency, including customer bill savings, improved economic competitiveness, water savings, and reductions in other air pollutant emissions.

Just Say, “No Regrets”

In many states, leaders understand this opportunity and are acting on it concretely. In a special message to his constituents on energy and the environment, Michigan Governor Rick Snyder said:

“The hard part is that we don’t know exactly what our future will hold and what challenges to our energy and environmental futures we will face. But that is no excuse for standing still or failing to be proactive. What we need to do is identify those actions or decisions that are adaptable. These are solutions that are good for Michigan, not just in one possible future, but in many possible futures. We have a lot of opportunities to take action today—action that is “no-regrets” even if things turn out differently than we predict. … Energy efficiency is the best example of a no-regrets policy Michigan can have. It makes us more reliable, more affordable and protects our environment.”

Energy efficiency policies and programs offer a “no regrets” approach to delivering reliable, affordable electricity, while meeting the Clean Power Plan and other environmental policies. Even states intending to oppose EPA in the courts will be better positioned to comply, if necessary at a later date, if they have well-developed and supported energy efficiency programs, supply chains, methodologies, and expertise. EPA assumed that a gradual ramping up of state energy efficiency savings is feasible, and that assumption is baked into each state’s target. If states delay or ramp down their energy efficiency programs until they get legal certainty, they could suffer later by having to ramp those programs up more quickly or by paying greater than necessary compliance costs. Not only could this prove to be a costly mistake, it may be more destructive because a ramp down—especially if it is abrupt—can harm relationships with the contractors and trade allies that efficiency programs need as partners.

Failing to Plan = Planning to Fail

Those who advocate that states should “just say no” or should “wait and see” mistakenly equate planning for a variety of legal outcomes with accepting defeat. The viewpoint that “analyzing options and planning for compliance could end up being a costly, wasted effort, if the rules are never implemented,” ignores the fact that utilities and regulators develop and update long-range plans as a routine matter of business. Factoring the possibility of greenhouse gas regulations into those planning processes is a relatively simple and inexpensive matter, differing only a little from long-standing practices. We recommend that states do exactly that: in integrated resource planning proceedings or certificate of need reviews for large projects, states should analyze various Clean Power Plan compliance scenarios, and consider all available resource options, particularly energy efficiency. This essential best practice will position states to comply with the Clean Power Plan at least-cost to ratepayers.