When homes and buildings are first constructed, they must meet the building code in place at the time of construction. The median age of U.S. homes is 39 years, which means that most homes are decades out of date on the most efficient and cost-saving housing technologies. The replacement rate of buildings — demolition and new construction — is less than 2% per year, leaving a vast amount of outdated technologies in current building stock. This makes it clear that to modernize existing buildings, update appliances and mitigate the impacts of climate change, we must implement policy solutions beyond building codes that address the energy and carbon emissions of existing buildings.

Modernizing existing buildings can also save energy, save money and lead to more jobs. More than $279 billion could be invested in existing U.S. building retrofits, according to Deutsche Bank, yielding more than $1 trillion of energy savings over 10 years. The savings potential is equivalent to 30% of the total annual electricity spending in the United States and would create thousands of jobs.

Understanding this landscape, cities and states are increasingly pursuing mandatory policies that require improved energy and emissions performance across their existing building stock. The most comprehensive of these policies is the building performance standard (BPS), in which performance thresholds are set that building owners must meet at a specified time or when a triggering event occurs, such as a major renovation. A BPS can be designed to optimize the energy use in older buildings, as well as protect and conserve water, enhance indoor air quality, reduce waste and air pollution and create jobs. The power of a BPS comes from selecting the right metrics and setting the right targets — ones that align with the goals of a jurisdiction and drive action to ensure that investments achieve long-term compliance and emissions reductions.

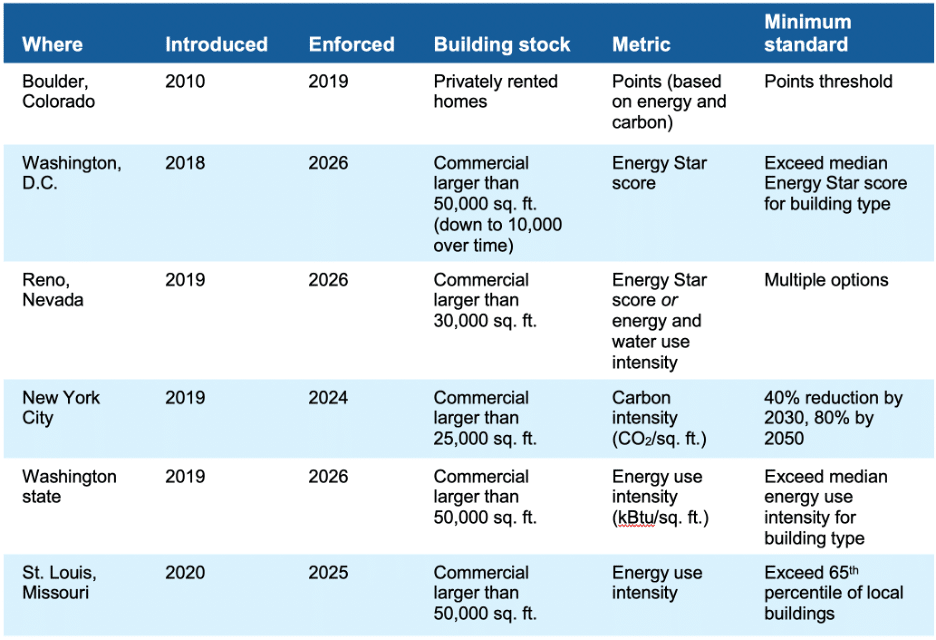

Today, seven local jurisdictions (Boston; Chula Vista, California; Denver; the District of Columbia; Montgomery County, Maryland; New York City; and St. Louis) and three states (Colorado, Maryland and Washington) have enacted building performance standards. Capitalizing on this momentum, a growing number of cities and states are considering such standards to meet economic, equity, public health, climate and financial goals.

Considerations in Developing Building Performance Standards

Building performance standards will affect a large number of building owners, tenants and residents, so policymakers need to ensure that compliance is feasible for everyone and addresses broader priorities beyond climate. Key considerations in shaping a BPS include:

- Alignment with established commitments and long-term goals.

- Regulatory certainty over time.

- Consistency of language and terms.

- Ability to drive early action.

- Accommodation of building life cycle events.

- Transparency and ease of implementation and compliance.

- Social and racial equity.

- Jobs and economic growth.

The central component of a BPS is the performance standard and associated metric, which must be met to comply with the law. A design may incorporate multiple standards so that all aspects of high-performance buildings are addressed.

One of the first decisions in designing a BPS is the type of primary metric to use. The BPS can measure energy use (site or source energy use) or carbon emissions and can incorporate time of use.

Several metrics are commonly applied in the development of a BPS. Those are summarized in the table below, adapted by New Buildings Institute.

Other key considerations in defining BPS metrics include:

- Electrification: The BPS can be designed to support electrification of end uses by incorporating carbon metrics or measuring on-site fossil fuel combustion.

- Grid interactivity: The BPS can incorporate requirements that facilitate grid interactivity, including the installation of a building automation system that supports demand response.

- Resiliency: The BPS can include components that evaluate a building’s passive survivability during disasters and capacity to serve as a community resource in responding to disasters.

- Public health: The BPS can include metrics that directly impact the health of building occupants, including indoor air quality and radon mitigation.

- Solid waste and water: The BPS can incorporate additional non-energy sustainability metrics, including solid waste, recycling and water use.

Understanding the complexity of designing and implementing these policies and the urgent need to address greenhouse gas emissions from the built environment, RAP has worked together with expert organizations to pull together key resources and information for policymakers looking to implement building performance policies within their jurisdiction.

Legislative Toolkit and Additional Resources

The Building Modernization Toolkit consolidates key considerations for policymakers in designing and implementing a BPS. These include contextual information about the impacts and benefits of building performance policies, legislative pathways for improving the performance of a building, and example policy language from jurisdictions that have already implemented a BPS and other performance policies. The toolkit also includes information on energy codes and other policies for modernizing buildings.

States and cities that are seeking to enact BPS policies have additional resources to draw from on top of the RAP legislative toolkit. New Buildings Institute has published several blogs explaining aspects and application of BPS policy.

- Laying out the case for investing in existing building efficiency with building performance standards as a policy strategy.

- Explaining key aspects of BPS policy, including metrics and goals, how to determine the parameters of the standard and which buildings should be covered, as well as compliance considerations.

- Presenting additional benefits jurisdictions can derive from energy efficiency investments in existing buildings, including measures that are known to also improve the health and safety of residents and create better-paying jobs that fuel local economies.

- Future-proofing a building or portfolio by designing with the end in mind, including plans to meet future zero-energy and carbon targets in a clearly articulated time frame.

Additionally, New Buildings Institute has co-authored a framework for governments to consider in designing a BPS and a paper on BPS variables and has developed a dashboard to assist jurisdictions in setting targets for a BPS.